as wasʜɪɴɢtoɴ deveʟoped , Southwest

became its main working, waterfront community.

Its wharves received travelers, food and building

materials, slaves and migrants, and weapons for

the new City of Washington. Ships were built and

repaired here. The port was particularly busy during the Civil War, when Washington served as the

Union Army’s headquarters and supply center.

By 1900 this bustling neighborhood was densely

built, with a working-class community of some

35,000. They were modest people of all backgrounds: European immigrants, urban African

Americans, and migrants from nearby rural areas.

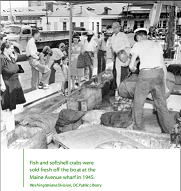

The waterfront was a major marketplace, where

Chesapeake Bay watermen tied up and sold fresh

seafood and farmers delivered fresh produce.

Waterfront warehouses held these commodities

for distribution throughout the city.

With its small town atm o s ph ere , and mode s t

bri ck and wooden bu i l d i n gs and shop s , So ut hwe s t

was homey and self-sufficient.

As real estate devel opers open ed other areas of t h e

c i ty, So ut hwest qu i et ly aged . Its modest rowh o u ses, elegant older homes, and cramped alley

dwellings became run down and overcrowded.

By the 1930s, reformers called Southwest obsolete.

News stories declared it was located “shamefully

. ..in the shadow of the Capitol.” The Washington

Post led a campaign to tear down Southwest a n d

start over. The press published photographs of

urban blight,” ironically situated next to the nearby U.S. Capitol. Consequently nearly all of Old

Southwest— 560 acres of buildings and trees—

was ra zed bet ween 1954 and 1960. In its place a

much-admired “new town in the city” was built.

But the forced dispersal of 23 , 500 people con ti nu e s

to raise important questions about the benefits

of urban renewal.

back to map